Causes, detection, and recovery strategies for knife makers

By Yashar Mousavand, Lead instructor

What this page covers

This page explains austenite grain growth as it applies to blades. It focuses on the variables a maker can control: temperature, time, section thickness, atmosphere, and steel chemistry. Every claim that depends on external data is backed by references so readers can verify the details.

Executive summary

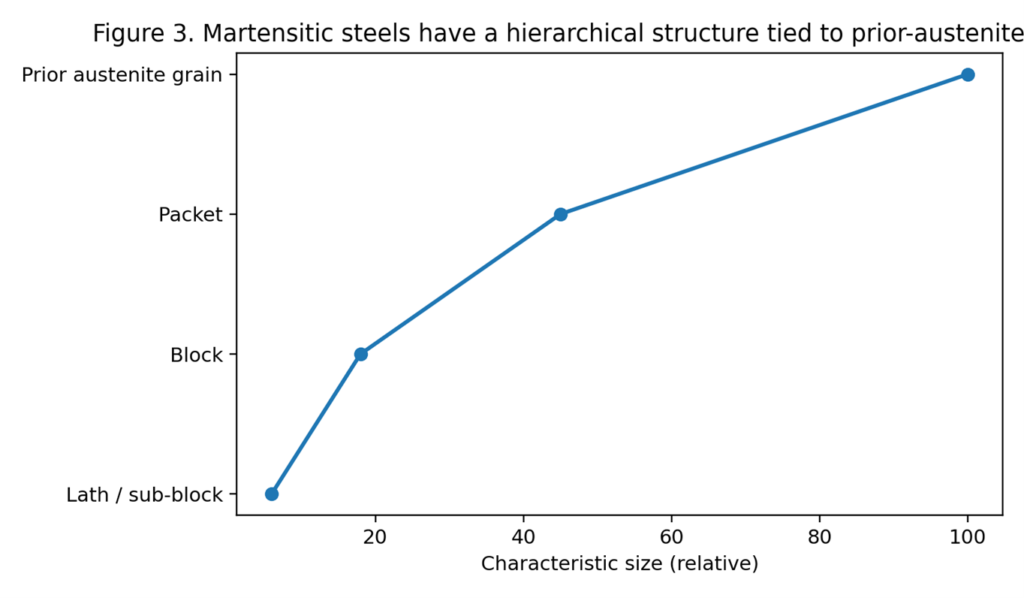

- Prior-austenite grain size (PAGS) is a controlling dimension in martensitic steels. It influences packet and block sizes, and it strongly affects toughness and chipping resistance.

- Austenite grains grow because grain boundaries carry energy. Growth reduces total boundary area, but is resisted by pinning particles and solute drag.

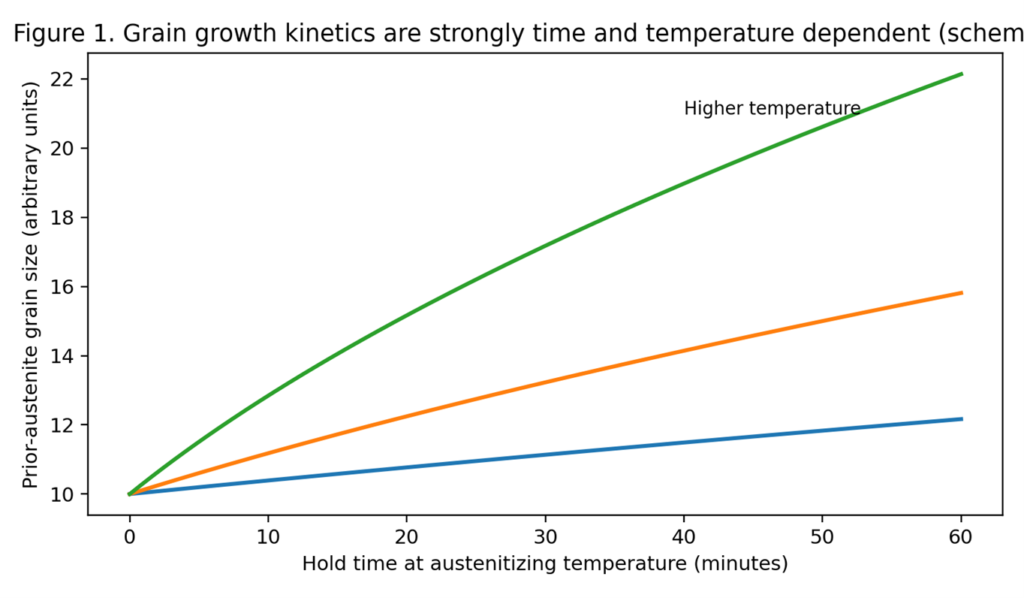

- Grain growth kinetics are often modeled as D^n – D0^n = Kt, with K following Arrhenius temperature dependence. Translation: a small temperature overshoot can do the same damage as a long soak.

- Overheating can trigger abnormal grain growth if pinning particles dissolve or become ineffective. Abnormal growth is more destructive than normal coarsening because it produces a mixed population of very large grains.

- Detection ranges from lab grade methods (prior-austenite boundary revelation and ASTM E112 measurement) to shop indicators (fracture surface character and repeatable toughness tests).

- Recovery is possible only if you have not burned the steel. Mild coarsening can often be corrected by controlled normalizing or grain-refining thermal cycles. Severe overheating near incipient melting is not recoverable in a knife context.

1. Define the grain you are trying to control

1.1 Prior-austenite grain size vs what you see in martensite

When makers say grain size, they usually mean prior-austenite grain size. After quenching, martensite is formed inside the prior-austenite grains as packets, blocks, and laths. This hierarchy means that changing PAGS typically shifts the scale of several downstream features, not just one. [R1]

Figure 3 is a schematic of this hierarchy.

1.2 Why PAGS matters to knife performance

For a knife, the practical impact of coarse PAGS is usually reduced tolerance for defects: lower impact energy, higher brittle transition behavior, and easier crack propagation across large grains. Studies on martensitic and low alloy steels commonly show that refined PAGS improves strength and toughness metrics, though the exact controlling level can be PAGS, packet size, or both depending on the alloy and processing. [R1] [R2]

2. The physics: why austenite grains grow

2.1 Driving force: boundary energy and curvature

Grain boundaries carry excess energy. At high temperature, boundaries migrate to reduce total boundary area. Smaller grains have more boundary area per unit volume, so the system lowers energy by consuming small grains and growing larger ones. This is the fundamental driver of normal grain growth. [R3]

2.2 Kinetics: the growth law you can use for risk thinking

A widely used engineering form for normal grain growth is:

D^n – D0^n = K t

where D is average grain size, D0 is initial grain size, n is the growth exponent, K is a temperature dependent rate constant, and t is time. [R4]

K typically increases rapidly with temperature and is often represented with Arrhenius behavior:

K = K0 · exp(-Q / (R T))

This is why a short, hot overshoot can cause comparable coarsening to a longer, lower soak. [R4]

Figure 1 is a schematic showing the combined effect of time and temperature.

2.3 What stops grain growth: solute drag and pinning

Two major brakes on boundary motion are:

• Solute drag: certain dissolved elements segregate to boundaries and slow migration.

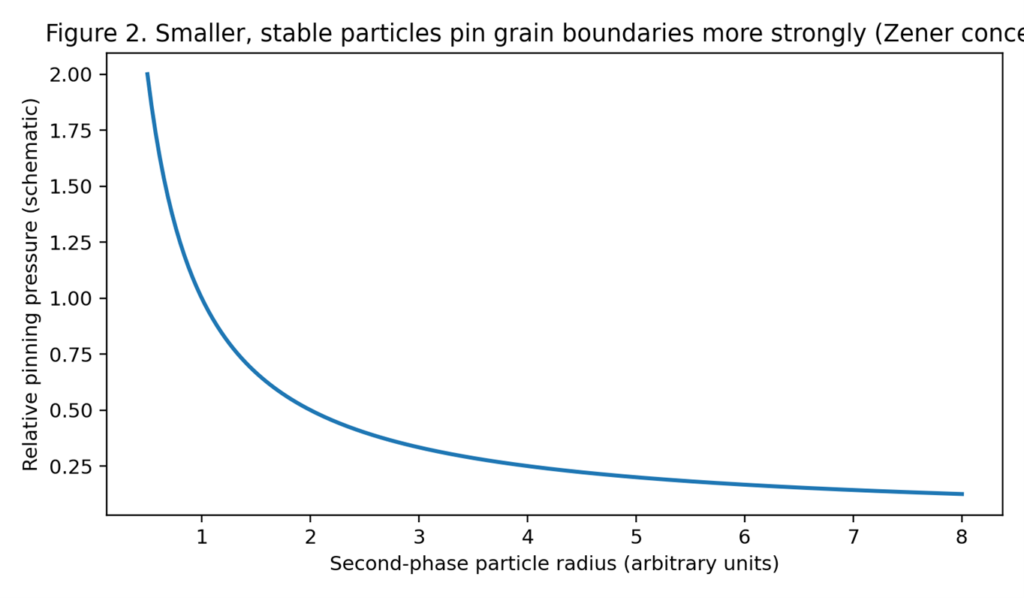

• Zener pinning: fine precipitates and carbides physically pin boundaries and add a resisting pressure.

The balance between driving force and these brakes determines whether grains stay fine or coarsen rapidly. [R5] [R6]

Zener pinning strength scales inversely with particle size for a given volume fraction. Fine, stable particles are powerful. If the particles dissolve at high temperature, pinning can collapse and grain growth accelerates.

Figure 2 is a schematic of the Zener concept.

You might also like : Technical Knife Forging and Heat Treat Handbook for Bushcraft

3. Blade specific causes of austenite grain growth

3.1 Austenitizing too hot or too long

For heat treat, the most common cause is exceeding the temperature-time window that the steel was designed for. Heat Treat Doctor notes that austenite grains are very small when first formed but grow as time and temperature increase, and that holding just above the upper critical maintains smaller grain relative to higher temperatures. [R7]

Knife Steel Nerds shows clear images of increased prior-austenite grain size with higher austenitizing temperature in Uddeholm Caldie, and notes that the higher temperature used in the example is above the datasheet recommendation, with a corresponding drop in toughness. [R8]

3.2 Forging overheating and local hotspots

In a forge, temperature is spatially non-uniform. Local hotspots are common at the burner flame path and at the forge floor. A blade can exceed safe temperature locally even when the overall color seems acceptable. Because K in the growth law is temperature sensitive, localized overheating can create localized coarse grains that behave like weak links.

3.3 Carbide dissolution and pinning collapse

Many knife steels rely on carbides and nitrides for grain control. If you heat high enough that these particles dissolve or coarsen rapidly, grain boundaries lose pinning and can move quickly. Reviews of grain growth emphasize Zener pinning and solute effects as key controls, and experimental work shows precipitate morphology can strongly alter grain growth resistance. [R5] [R6]

In high carbon steels with grain boundary cementite networks, the dissolution behavior can change transformation and grain growth behavior. Recent work analyzes cementite dissolution effects on austenite grain growth in high carbon low alloy steels. [R9]

3.4 Abnormal grain growth

Abnormal grain growth is when a few grains grow much larger than the rest, producing a highly non-uniform size distribution. This is often worse than uniform coarsening because very large grains can dominate crack paths. Overviews of normal and abnormal growth highlight that abnormal growth is associated with changes in pinning, solute drag, or boundary mobility distributions. [R10]

For makers, the practical trigger is often overheating into a range where pinning particles become ineffective, followed by a hold long enough for a few grains to run away.

4. Detection: how to know you have a grain growth problem

4.1 Best practice: measure PAGS, do not guess

If the blade is important or you are developing a process, the correct approach is to measure prior-austenite grain size. ASTM E112 describes standard methods (comparison charts, intercept, planimetric) for determining average grain size. [R11] In practice, most makers outsource this to a metallography lab unless they already have preparation equipment.

4.2 Revealing prior-austenite grain boundaries

Revealing prior-austenite grain boundaries in quenched martensitic structures is not trivial. Published work notes that picric acid based etchants can delineate boundaries, but picric acid is toxic and explosive and is regulated. A newer study reports a method to recognize boundaries using nital as a safer alternative. [R12]

Practical recommendation: do not improvise hazardous etchants. If you need PAGS, use a qualified lab or a vetted, safety-compliant shop procedure.

4.3 EBSD reconstruction and thermal etching

For research-grade measurement, EBSD reconstruction can estimate the original austenite grain structure from transformed microstructures, and comparative work discusses accuracy tradeoffs among etching, EBSD, and thermal methods. [R13]

4.4 Shop indicators that correlate with coarse grain

If you do not have metallography, you can still build evidence:

• Fracture surface character: coarse grains often produce a more crystalline, granular appearance on brittle fractures, but this is only a rough indicator.

• Repeatable toughness coupons: compare bend or impact behavior of coupons heat treated at two different austenitizing temperatures while holding hardness similar.

• Edge behavior at equal hardness: unexpected microchipping with otherwise sound geometry can be a sign of reduced toughness from coarse microstructure.

These are correlations, not proofs. Use them to trigger deeper measurement, not to declare a conclusion.

5. Prevention: process controls that keep grain fine

5.1 Control temperature with instruments, not color

Grain growth risk is dominated by peak temperature and time at peak. A thermocouple in the hot zone and a disciplined soak timer provide more control than relying on color. If you use an IR thermometer, emissivity changes with scale, so you must keep surface condition consistent.

5.2 Do not soak unless your steel requires it

Soaking is sometimes required to dissolve carbides and obtain target hardness, especially in high alloy steels. However, every extra minute is paid in grain growth risk. The correct approach is steel specific: follow the datasheet and validate with hardness and microstructure. Knife Steel Nerds emphasizes that grain size, carbon in solution, and carbide volume are all controlled by time and temperature. [R14]

5.3 Use preheat stages where recommended

Multi-step preheats reduce thermal gradients, reduce distortion, and can influence carbide dissolution behavior. They are not superstition. They are a way to bring the whole section into a controlled thermal state before the austenitizing step. [R15]

5.4 Steel choice and grain control practice

Steelmaking practice matters. A technical overview of austenitizing notes that steels produced with fine-grained practice differ from coarse-grained practice in how grain size evolves with austenitizing temperature. [R16] For makers, the takeaway is simple: buy from reputable suppliers, and do not assume that two visually similar bars have identical grain growth behavior.

6. Recovery strategies after overheating

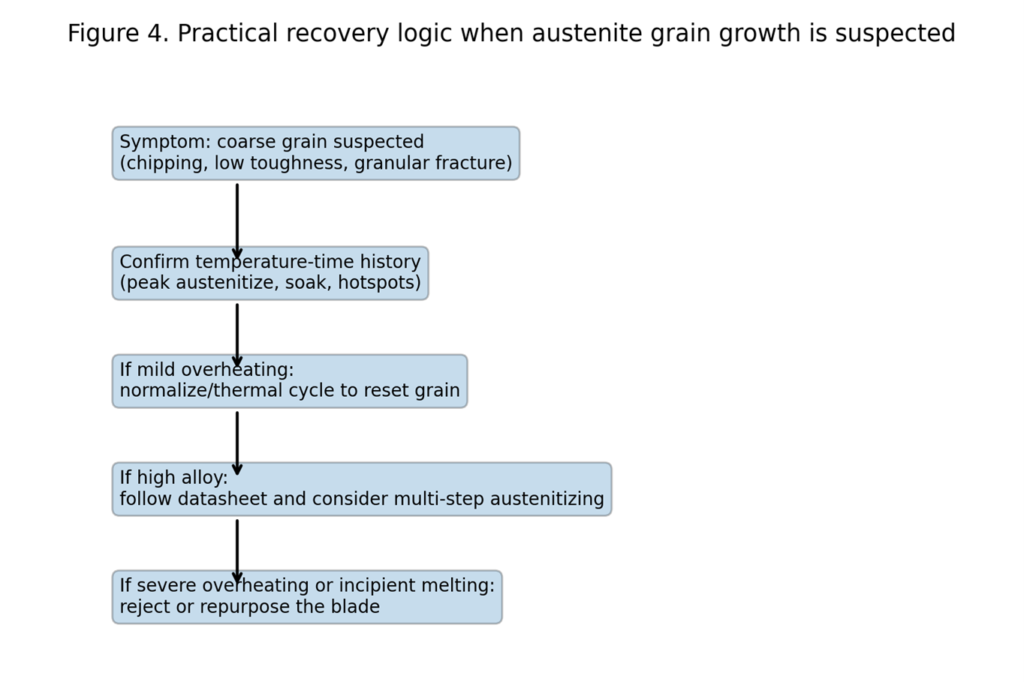

6.1 First triage: decide if recovery is realistic

Not all overheating is recoverable. If the steel was heated near incipient melting (burning), grain boundary damage can occur and toughness may not return. In knife work, the conservative decision is to reject or repurpose severely overheated pieces.

Figure 4 summarizes a practical recovery logic.

6.2 Mild coarsening: normalize or grain-refine cycles

If overheating was mild, you can often reset microstructure through controlled thermal cycling. The mechanism is re-austenitization from a refined starting structure, followed by air cooling (normalizing) to form fine transformation products that seed finer austenite on the next cycle. ABS educational material discusses normalizing practices used by bladesmiths to smooth and correct forging introduced microstructural chaos. [R17]

Best practice is to base cycles around the steel’s critical temperatures rather than fixed numbers:

• First cycle: heat slightly above the upper critical so austenite forms fully.

• Cool in still air to room temperature.

• Subsequent cycles: slightly lower peak temperatures to reduce growth while still transforming.

Then perform the final austenitize at the lowest temperature that meets hardness and carbide solution requirements.

6.3 High alloy and stainless: consider multi-step austenitizing instead of pushing hotter

Some steels tempt makers into higher austenitizing temperatures to increase hardness or reduce carbides, but the toughness penalty can be large. Knife Steel Nerds describes multi-step austenitizing, where a higher temperature step is followed by a lower austenitizing step, achieving a compromise between carbide solution and grain size for some steels. [R15]

This is not a generic recipe. It is a strategy to be validated steel by steel. Start with the manufacturer recommended process, then adjust only after you can measure hardness, retained austenite, and toughness proxies.

6.4 Practical shop validation: confirm recovery with repeatable tests

Recovery is only real if performance returns. A maker validation loop can be:

1) Make two identical coupons from the same bar.

2) Heat treat one with the suspected overheating condition and one with the corrected process.

3) Match hardness as closely as possible.

4) Compare edge stability and toughness with controlled tests (bending, impact, and controlled cutting plus microchipping inspection).

If you cannot match hardness, you cannot isolate grain size as the variable.

7. A process control checklist for blades

- Record peak temperature and soak time for every heat treat batch.

- Avoid unknown forge hot spots: map your forge with a thermocouple and learn where peak temperature occurs.

- Do not heat above datasheet temperatures to chase hardness without measuring the toughness cost.

- If you must austenitize high, reduce time at peak and consider strategies such as multi-step austenitizing where supported by data.

- After heavy forging, normalize with discipline. Do not skip it if you care about toughness.

- Treat PAGS measurement as a development tool. A single lab report can save months of guessing.

About the author

Yashar Mousavand writes technical bushcraft and bladesmithing content focused on measurable variables and reproducible processes. His approach is to link shop observations to metallurgy, cite primary sources when numbers matter, and provide validation methods makers can actually run.

References

R1: The Effects of Prior Austenite Grain Refinement on Strength and Toughness (Metals, MDPI): https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4701/12/1/28

R2: Effect of Microstructure Refinement on Strength and Toughness of Martensitic Steel (JMST, 2007): https://www.jmst.org/EN/Y2007/V23/I05/659

R3: Austenite Grain Growth overview (ScienceDirect Topics): https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/austenite-grain-growth

R4: On the Modelling of Austenite Grain Growth in Micro-alloyed Steel S700MC (PDF): https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Norbert-Enzinger/publication/292091420_On_the_Modelling_of_Austenite_Grain_Growth_in_Micro-alloyed_Steel_S700MC/links/56a8df2e08aec57514c3e7bb/On-the-Modelling-of-Austenite-Grain-Growth-in-Micro-alloyed-Steel-S700MC.pdf

R5: Recent advances in kinetics of normal and abnormal grain growth (Springer): https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43452-021-00185-8

R6: Influence of Precipitate Morphology on Austenite Grain Growth (Materials, MDPI): https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/9/3176

R7: Grain Size specifics (Heat Treat Doctor PDF): https://heat-treat-doctor.com/documents/GrainSize.pdf

R8: Austenitizing Part 2: Effects on Properties (Knife Steel Nerds): https://knifesteelnerds.com/2018/03/01/austenitizing-part-2-effects-on-properties/

R9: Effect of network cementite dissolution on austenite grain growth (ScienceDirect): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S223878542400574X

R10: In-situ Observation of Abnormal Grain Growth of Austenite (ISIJ International PDF): https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/isijinternational/61/11/61_ISIJINT-2021-239/_pdf/-char/en

R11: ASTM E112 Standard Test Methods for Determining Average Grain Size (ASTM): https://store.astm.org/standards/e112

R12: Prior austenite grain boundary recognition in martensite microstructure using Nital (Springer): https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42243-023-00947-z

R13: Prior austenite grain measurement comparison (Mat. Char. preprint PDF): https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/213188/1/PAG%20Mat%20Char%20Paper.pdf

R14: Austenitizing Part 1: What it is (Knife Steel Nerds): https://knifesteelnerds.wordpress.com/2018/02/28/austenitizing-part-1-what-it-is/

R15: Austenitizing Part 3: Multi-Step Austenitizing (Knife Steel Nerds): https://knifesteelnerds.com/2018/03/07/austenitizing-part-3-multi-step-austenitizing/

R16: Austenitizing in Steels (Speer, Colorado School of Mines PDF): https://wpfiles.mines.edu/wp-content/uploads/aspprc/ResearchMaterials/Publications/566-Speer.pdf

R17: Some Very Basic Confusion On Normalizing And Annealing (American Bladesmith Society): https://www.americanbladesmith.org/community/heat-treating-101/some-very-basic-confusion-on-normalizing-and-annealing/