Why deformation schedule matters in forging and thermomechanical processing of blade steels

By Yashar Mousavand

How to use this page

This article explains why the sequence of reductions, the time between them, and the temperature and strain rate history in knife forging can change microstructure even when the steel grade is identical. The focus is dynamic restoration: dynamic recovery (DRV), dynamic recrystallization (DRX), and the post deformation processes that follow (static and metadynamic recrystallization). If you want repeatable toughness and edge stability, you need a schedule, not just a target temperature.

Executive summary

- DRX is not a switch that flips at a single temperature. It is a strain activated renewal process that depends on temperature, strain rate, initial grain size, and alloy chemistry.

- The onset of DRX occurs at a critical strain εc, which happens before the peak stress in typical constant strain rate tests. Poliak and Jonas showed εc can be detected from an inflection in a work hardening rate versus stress plot. [R3] [R4]

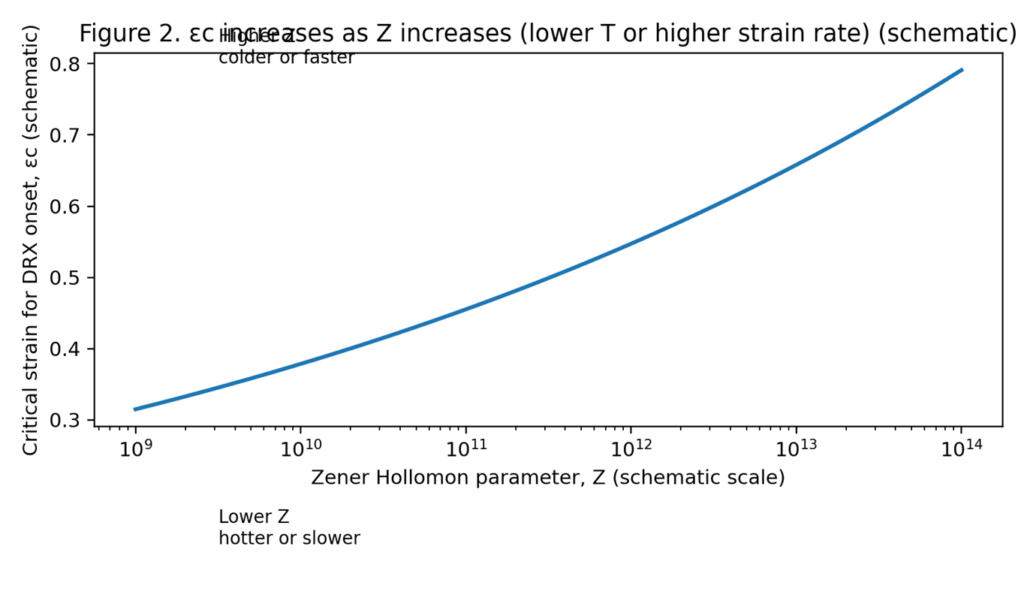

- A common way to think about temperature and strain rate together is the Zener Hollomon parameter Z = ε_dot · exp(Q/(R·T)). Higher Z means colder or faster deformation and generally raises the strain required to trigger DRX. [R5] [R6]

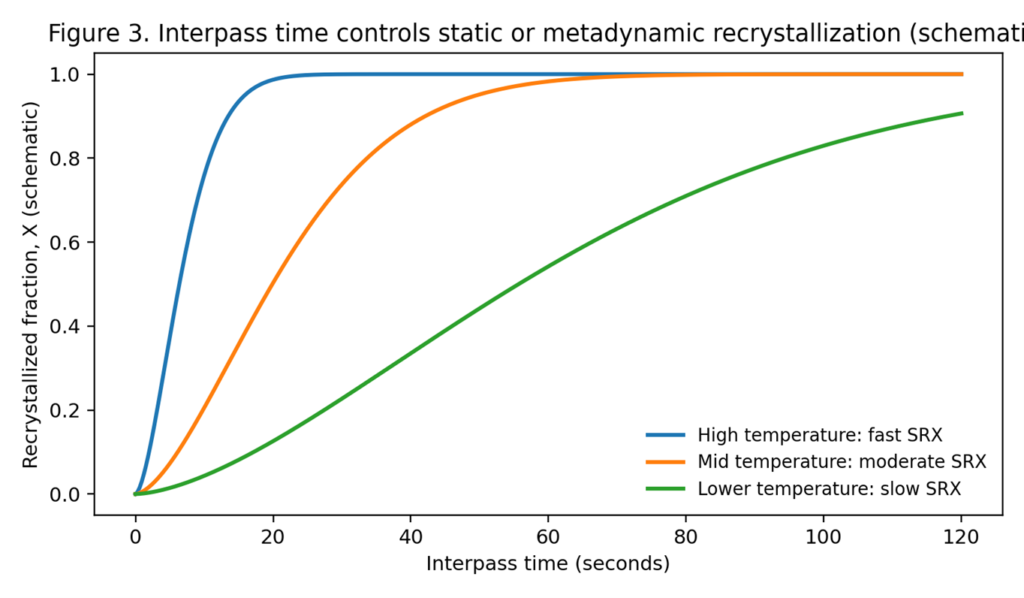

- Reduction timing matters because between passes the steel can undergo static recrystallization (SRX) or metadynamic recrystallization (MDRX). These can reset dislocation structure and grain size, or produce partial recrystallization that makes microstructure less uniform. [R7]

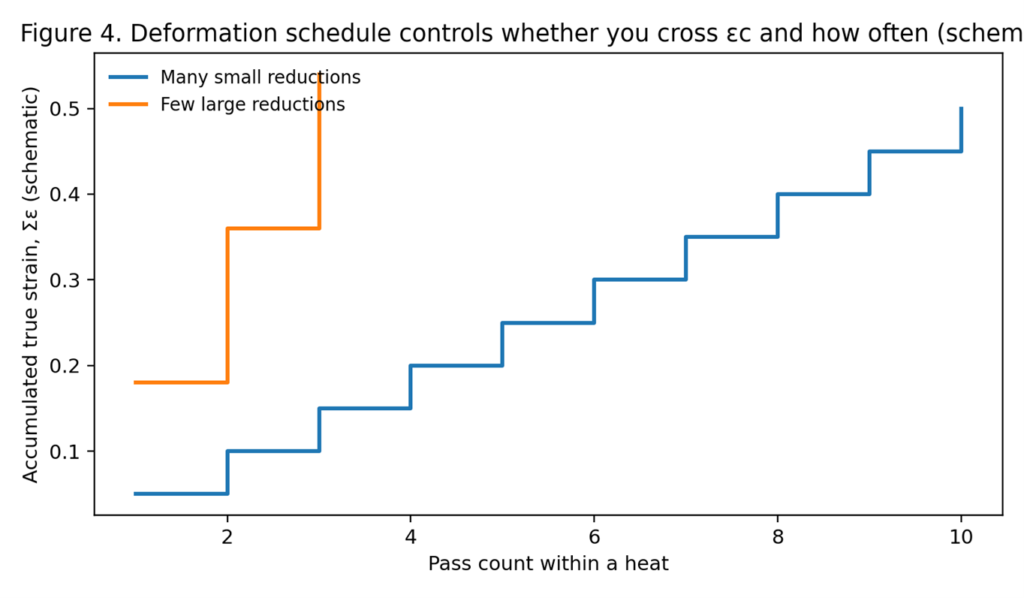

- In blades, small deformations spread across long heats can fail to reach εc while still spending time at high temperature, which increases grain growth risk without the compensating refinement benefit.

- The practical goal is to match your deformation schedule to the restoration mechanism you want: DRX during hot work for refinement, or controlled SRX between passes when appropriate, while minimizing time at excessive temperature.

1. Dynamic restoration in steels: DRV vs DRX

1.1 What dynamic restoration means

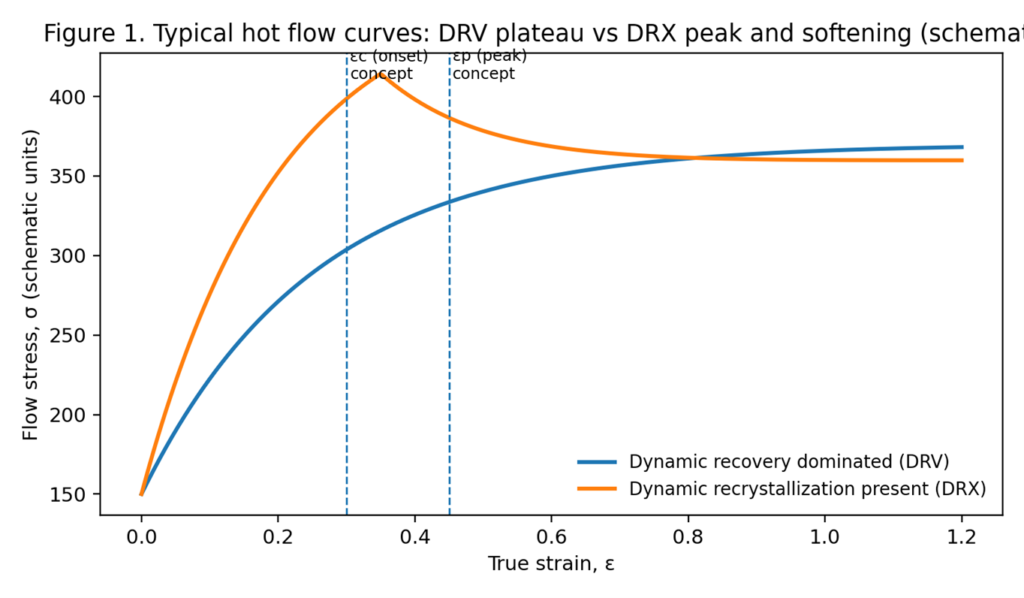

During hot deformation, flow stress rises because dislocation density increases (work hardening). At the same time, high temperature enables mechanisms that reduce stored dislocation energy. The family of in process softening mechanisms is called dynamic restoration. A core reference text notes that dynamic recovery and dynamic recrystallization occur during hot rolling, extrusion, and forging and they matter because they reduce flow stress and influence texture and grain size. [R1]

1.2 Dynamic recovery

Dynamic recovery is progressive rearrangement and annihilation of dislocations during deformation. It forms subgrains and often leads to a stress strain curve that rises and then reaches a steady state plateau. The same reference describes this plateau behavior and ties it to the balance between hardening and recovery. [R1]

1.3 Dynamic recrystallization

Dynamic recrystallization creates new, low dislocation grains during deformation. In many steels, especially in austenite, DRX is discontinuous: nucleation occurs at boundaries followed by growth, producing a characteristic stress peak and then softening toward a lower steady state stress. In ferrite, continuous mechanisms can be more prominent in some cases. Experimental work on dual phase steels reports continuous DRX in ferrite and discontinuous DRX in austenite under certain hot deformation conditions. [R8]

Figure 1 shows the typical difference between DRV dominated and DRX influenced flow curves.

2. Why schedule matters: the critical strain εc and the flow curve

2.1 DRX begins before the peak stress

In constant strain rate tests, DRX begins at a critical strain εc that is lower than the strain at peak stress εp. The critical strain corresponds to reaching a critical dislocation density or stored energy level. A review focused on critical strain explains that DRX initiates before the peak and defines εc and the associated critical stress. [R4]

2.2 How εc is identified: the Poliak Jonas criterion

Poliak and Jonas proposed a detection method using the work hardening rate θ = dσ/dε. The onset of DRX can be identified from an inflection point in a θ versus σ plot. This approach is widely used because it can be applied to flow curve data without direct microstructural observation. [R3] [R9]

2.3 Why small reductions can be worse than you expect

If each pass contributes a strain increment that never reaches εc, you can spend significant time at high temperature accumulating grain growth risk while never triggering the refinement associated with DRX. This is a schedule problem, not a steel problem.

3. Temperature and strain rate together: Zener Hollomon parameter Z

3.1 The equation and the interpretation

Zener Hollomon parameter combines strain rate and temperature into one variable:

Z = ε_dot · exp(Q / (R · T))

where ε_dot is strain rate, Q is activation energy for hot deformation, R is the gas constant, and T is absolute temperature. Higher Z corresponds to lower temperature or higher strain rate. [R5]

3.2 How Z shifts DRX behavior

As Z increases, the flow stress increases and the strain required to initiate DRX generally increases. A technical report on hot working of steels gives a common modeling form where εc depends on initial grain size and Z, for example εc = 0.65 · A · D0^m · Z^q in C Mn steels, emphasizing that exponents and constants are composition dependent. [R6] The exact coefficients are alloy specific, but the directional effect is robust: colder or faster deformation raises εc.

Figure 2 is a schematic of εc increasing with Z.

4. Interpass time: static and metadynamic recrystallization between passes

4.1 SRX and MDRX

After a pass ends, the steel is still hot and still contains stored deformation energy. If temperature and time allow, static recrystallization can occur without further deformation. If DRX started during the pass, the post deformation process is often called metadynamic recrystallization. An ISIJ International paper discusses how controlling austenite recrystallization before transformation is central to microstructure refinement and describes delineating conditions for DRX as well as post deformation recrystallization. [R7]

4.2 Partial recrystallization is a uniformity problem

The ISIJ paper notes that when austenite is only partially recrystallized before transformation, deformed and recrystallized portions transform into different phases and at different rates, producing variable microstructure and properties. [R7] In blades, the same concept shows up as inconsistent toughness from one zone to another, especially when thickness varies.

Figure 3 illustrates interpass time effects (schematic).

5. Reduction timing: quantify schedule with true strain

5.1 True strain per pass

For schedule thinking, use a consistent strain measure. For thickness reduction under plane strain, a common approximation is:

ε = ln(h0 / h1)

where h0 is thickness before a pass and h1 after. This approximation is enough to compare passes and decide whether a given pass is likely to approach εc.

Two schedules that remove the same total thickness can have different metallurgical outcomes if one schedule concentrates strain into fewer passes.

Figure 4 compares accumulated strain for two pass styles (schematic).

5.2 Strain rate differences: hammer versus press

Hot working strain rates vary widely by tool. A hot deformation reference chapter notes hot working is generally carried out at strain rates about 1 to 100 s^-1. [R1] A power hammer tends toward higher effective strain rate than a hydraulic press. Higher strain rate increases Z, raises flow stress, and often pushes εc upward. Practical implication: the same temperature can produce DRX under press reductions but not under hammer blows if deformation is too fast or too cold.

6. Blade relevant scenarios: schedules and outcomes

6.1 Meaningful hot reductions with limited soak time

When you apply enough strain while the steel is fully austenitic and within a stable hot work range, you maximize the chance that DRX occurs and that the structure is renewed. This can reduce the sensitivity to initial grain size and prior processing history, although alloy chemistry still sets limits. [R1] [R4]

6.2 Many light corrections at high temperature

Repeated light corrections while the steel sits hot can be metallurgically inefficient: it may never cross εc but it extends time at temperature. That combination favors grain growth more than refinement.

6.3 Mixed section thickness and schedule mismatch

Blades are not uniform. The edge cools faster and sees higher local strain. The spine stays hotter. A schedule that is safe for the spine can be too cold for the edge, suppressing restoration and increasing cracking risk. Schedule design for blades is harder than for bars because Z is not uniform across the cross section.

7. Practical controls that tie schedule to metallurgy

7.1 Record what matters

A schedule is defined by: peak temperature, time at temperature, strain per pass, strain rate, and interpass time. If you record only one variable, record peak temperature. If you can record two, record peak temperature and time at peak. These are first order drivers for both grain growth and restoration mechanisms. [R1] [R5]

7.2 Processing map thinking as a concept

Processing maps use the dynamic materials model to identify stable hot work windows and instability regions from flow stress data. A Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A communication summarizes the processing map framework and warns about common computation errors. [R10] Most bladesmith shops cannot generate full maps, but the underlying idea is useful: some temperature and strain rate windows promote healthy flow and DRX, others promote defects.

7.3 Validate with controlled coupons

If you change a schedule and claim improvement, validate it. Make coupons from the same bar, run two schedules, match hardness, then compare toughness proxies. Without hardness matching, you cannot isolate grain or restoration effects.

8. Troubleshooting: symptoms that often point to schedule issues

- Hot work feels progressively harder within a heat: Hardening is outpacing dynamic restoration, often because temperature dropped or strain rate increased, pushing Z higher.

- Unexpected edge cracking during forging: Edge likely operated at higher Z (cooler or faster) than the spine, suppressing DRX and concentrating strain.

- Good hardness but low toughness or microchipping: Coarse grain from time at excessive temperature or schedules that promoted growth without refinement.

- Variability along the blade: Non uniform temperature and strain history produced partial recrystallization or mixed restoration states across thickness.

About the author

Yashar Mousavand is a bushcraft and survival instructor and the founder of Yashar Survival Academy. He teaches practical field skills and writes evidence based guides on knives, gear, and outdoor technique, focused on what reliably works in real conditions.

References

R1: Humphreys and Hatherly, Recrystallization and Related Annealing Phenomena, Chapter 13: Hot Deformation and Dynamic Restoration (PDF): https://users.encs.concordia.ca/~mmedraj/tmg-books/Recrystallization%20and%20Related%20Annealing%20Phenomena/Chapter%2013%20-%20Hot%20Deformation%20and%20Dynamic%20Restoration.pdf

R3: Poliak and Jonas, critical condition for DRX onset (PDF copy): https://archive.org/download/wikipedia-scholarly-sources-corpus/10.1016%252F0968-0004%252892%252990304-R.zip/10.1016%252F1359-6454%252895%252900146-7.pdf

R4: Metals (MDPI) review, Critical Strain for Dynamic Recrystallisation (2020): https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4701/10/1/135

R5: ScienceDirect Topics, Zener Hollomon parameter overview: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/zener-hollomon-parameter

R6: University of Pretoria report, critical strain dependence on grain size and Z in C Mn steels (PDF): https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstreams/6523b771-87fa-49b8-8ac8-b37dee2c8a83/download

R7: ISIJ International, Determining the Conditions for Dynamic Recrystallization in Hot Deformation of C Mn V Steels (PDF): https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/isijinternational/54/1/54_227/_pdf

R8: JMPE paper PDF, CDRX in ferrite and DDRX in austenite in a dual phase steel: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11665-022-07428-6.pdf

R9: Materials (MDPI), DRX model consistent with Poliak Jonas criterion: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/10/11/1259

R10: Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, processing maps framework and errors: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11661-020-05817-x