What changes above and below critical temperatures, and how a maker controls it

By Yashar Mousavand, Lead Instructor

How to use this page

This page is written for knife makers and bushcrafters who want forging to be repeatable, measurable, and tied to metallurgy. It answers one question: what actually changes when you forge below, within, or above the correct temperature window for your steel, and how do you control the outcome.

If you only remember one rule: do heavy forging while the steel is fully austenitic and hot enough to deform cleanly, and stop before the edge slips into the transformation band.

Executive summary

When temperatures drift outside the safe window, makers typically see more grain growth and brittle behavior on the hot side, and more distortion, edge tearing, and inconsistent hardening on the low or mixed phase side.

- The forging window is bounded by phase stability and by damage mechanisms. Below the lower critical, you are warm working ferrite and pearlite. Above the upper critical, you hot work austenite. At excessive temperatures, grain growth, oxidation, decarburization, and hot shortness begin to dominate.

- Critical temperatures are ranges, not single numbers. Ac1 and Ac3 or Acm shift with alloy chemistry and with heating rate. A fast forge heat can create a surface that is fully austenitic while the core is not.

- Dynamic recrystallization during austenitic hot work is a key reason forging can improve microstructure. It is also why forging at the correct temperature band is more forgiving than pushing steel too cold.

- Overheating is not only about scale. It can erase grain control (pinning) and, near the solidus, can create grain boundary damage that cannot be fixed by normalizing.

- Decarburization is a diffusion problem. Depth increases with time and temperature. If you cannot control atmosphere, you must budget grinding stock to remove decarb.

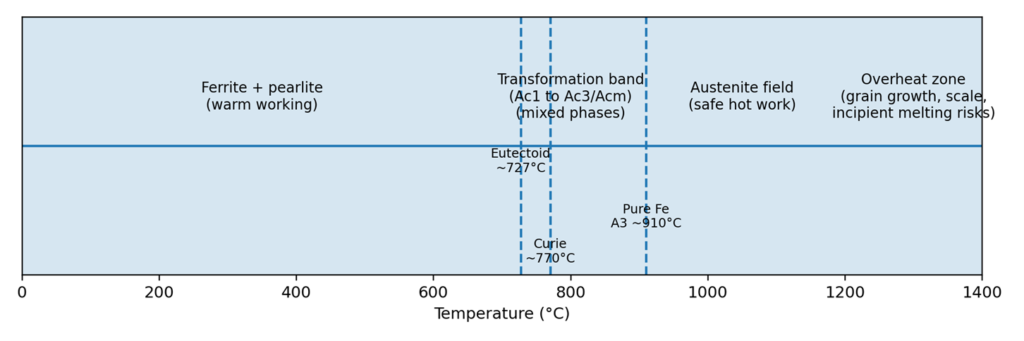

Figure 1. Regimes around critical temperatures (illustrative).

1. Critical temperatures and phase fields

1.1 The Fe-C basics you actually need in the forge

In plain language: steel behaves differently when its matrix is ferrite (bcc), austenite (fcc), or a mix. For many forging decisions you do not need a full phase diagram, but you must know where your steel is relative to the austenite transformation.

Key reference points for plain carbon steels include the eutectoid temperature near 727°C. Below it, austenite decomposes to ferrite plus cementite (often as pearlite). Above it, austenite is stable in a composition dependent range. This is the foundation of Ac1 and Ac3 behavior. [R1]

1.2 Ac, Ar, and Ae: why your steel does not transform at one fixed number

Notation:

• Ae1, Ae3, Aem are equilibrium temperatures from the phase diagram.

• Ac1, Ac3, Acm are the start and finish of transformation observed on heating.

• Ar1, Ar3, Arm are the start and finish observed on cooling.

Ac values are usually higher than Ae values because real heating is not infinitely slow. Ar values are usually lower than Ae values because cooling is not infinitely slow.

Why this matters in forging: if you heat fast (typical propane forge), the surface can reach austenite while the core lags. That means you can unknowingly forge a mixed phase cross section even if the outside looks hot.

1.3 Curie point: why the magnet test can fool you

Iron loses ferromagnetism at the Curie point, roughly 770°C. [R2] Austenite is also nonmagnetic. Depending on steel chemistry and how you heat it, the steel can go nonmagnetic because you crossed Curie, because you formed austenite, or because both happen close together. Treat magnet response as a rough checkpoint, not a setpoint.

once you know whether the steel is fully austenitic, mixed phase, or ferrite plus pearlite, the forging behavior stops feeling random and starts matching the phase you are actually deforming.

2. What forging temperature controls mechanically

2.1 Flow stress, strain rate, and why the press and hammer feel different

Hot deformation resistance depends on temperature and strain rate. Industrial hot working often uses temperature compensated strain rate concepts. A common parameter is the Zener-Hollomon parameter:

Z = ε_dot · exp(Q / (R · T))

where ε_dot is strain rate, Q is activation energy, R is the gas constant, and T is absolute temperature. [R10]

Higher strain rate or lower temperature both increase Z, which generally increases flow stress. Practical translation: a power hammer (high strain rate) needs a hotter workpiece than a slow press for the same reduction without damage.

2.2 Dynamic recovery and dynamic recrystallization in austenite

During hot work, dislocations build up (work hardening) and are also removed by recovery mechanisms. In many steels, especially when fully austenitic, dynamic recrystallization (DRX) occurs: new grains form during deformation and replace deformed grains. DRX is one reason the steel can soften after a peak stress and why hot working can refine microstructure. [R11]

Important practical consequence: when you forge in the austenite field at the correct temperature and with enough strain, the material is more likely to renew its grain structure. When you forge too cold, DRX is suppressed and deformation damage accumulates instead of being reset.

2.3 The temperature window is not only phase, it is damage control

A correct forging window is where you get the deformation you want while minimizing microstructural damage:

• too cold: tearing, edge splits, strain localization

• correct: uniform flow, DRX possible, defects can close

• too hot: grain growth, scale, decarb, hot shortness, incipient melting risks

the same amount of hammering can either refresh the structure through dynamic recrystallization or accumulate damage if you are too cold, so temperature is a microstructure control, not just a force control.

3. Microstructure and failure modes by temperature band

3.1 Below Ac1: warm working ferrite and pearlite

Below Ac1, the steel is not austenitic. Ferrite and pearlite deform differently, and the material does not have the same hot ductility as austenite. Thin edges cool rapidly and can drop into this regime during bevel forging even if the spine is still glowing.

Common outcomes when you forge here:

• edge fishtailing or splitting during drawing

• cracks initiating at carbides, cementite networks, inclusions, or sharp corners

• persistent banding or carbide networks that you hoped forging would fix

3.2 Ac1 to Ac3 or Acm: mixed phase deformation and strain localization

In the transformation band, only part of the microstructure is austenite at any moment. This creates a mechanical mismatch across thickness: surface regions can flow while the core resists. The mismatch concentrates strain and increases distortion and cracking risk.

This regime is a hidden cause behind many warps during forging: you are forging a two-material laminate made of hot austenite and cooler ferrite plus pearlite.

3.3 Above Ac3: austenite hot working and why it is forgiving

Above the upper critical, the matrix is austenite. The deformation is more uniform through cross section and the steel generally shows better hot ductility. In this band, you can do the heavy work: drawing tangs, setting bevels, and moving volume.

3.4 Too hot: grain growth, oxidation, decarb, and hot shortness

Overheating has multiple layers:

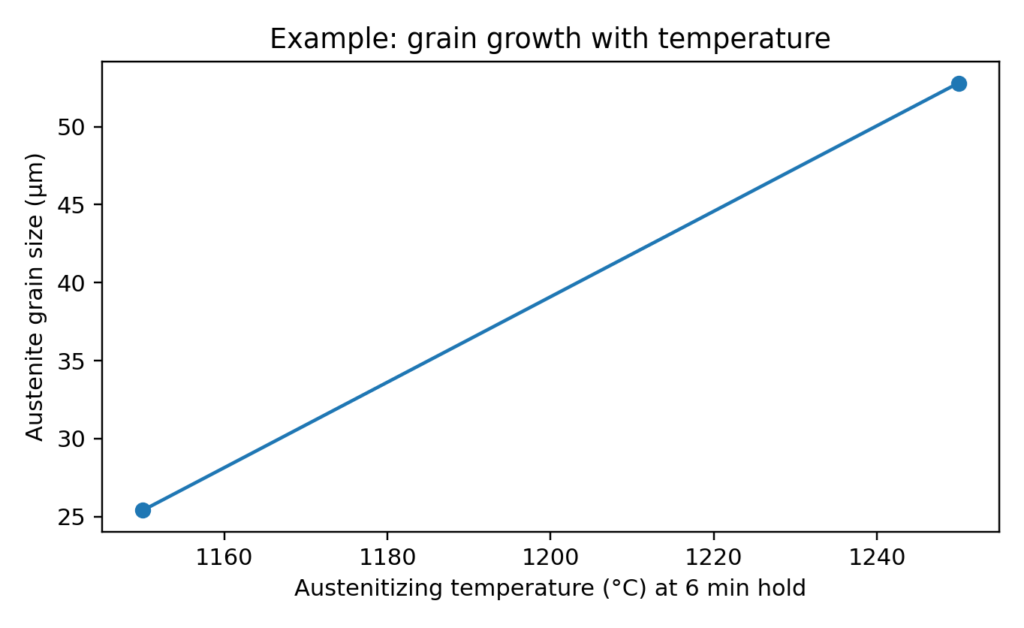

1) Grain growth accelerates with time and temperature. Grain control particles can dissolve at high temperatures and then grain size can jump. [R6]

2) Oxidation and decarburization accelerate. Carbon loss is not cosmetic. It creates a soft skin that will not harden.

3) Near the solidus, grain boundaries can weaken due to segregation or incipient melting. Studies of high temperature brittleness show brittle failure due to incipient melting at grain boundaries close to the solidus. [R12]

Figure 2. Example grain growth trend with higher austenitizing temperature (6 minute hold). [R7]

This figure is not a universal curve. It is an example of a general law: grain growth rates are strongly temperature dependent. The practical maker takeaway is simple: time at excessive heat is not free. If you overheat a bar while waiting for it to get bright, you may be paying with toughness later.

most blade problems start at the edge, and the edge is almost always in a different temperature band than the spine during real forging.

You Might also like: Technical Knife Forging and Heat Treat Handbook for Bushcraft

4. Scale and decarburization: the surface is part of your heat treat

4.1 What decarburization is

Decarburization is loss of carbon from the steel surface during exposure to oxidizing conditions at elevated temperatures. Carbon reacts at the surface to form CO and CO2, and carbon from beneath the surface diffuses outward to replenish what was lost. [R8]

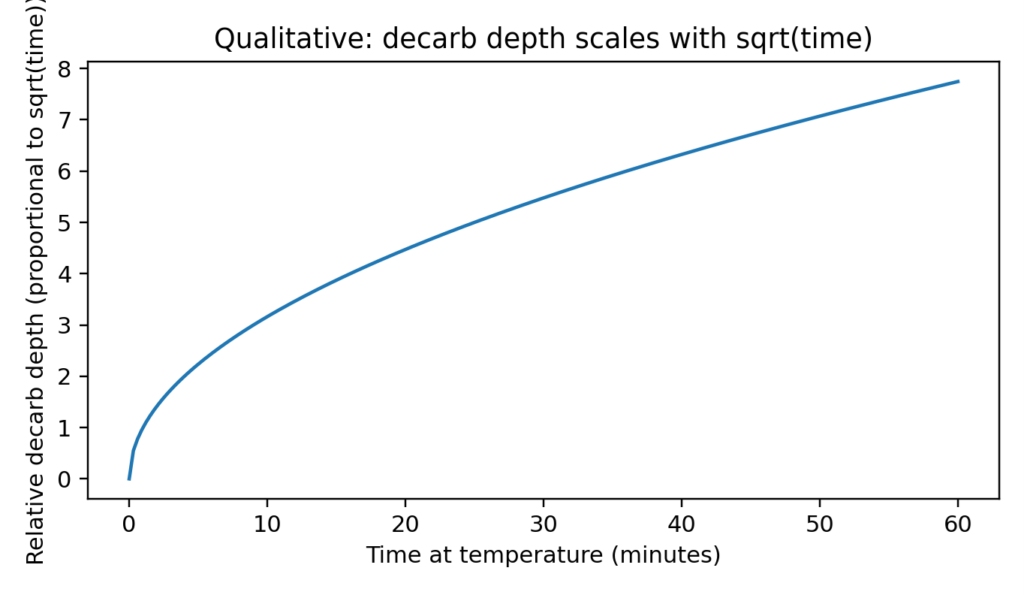

4.2 Why decarb depth scales with time and temperature

Diffusion driven processes typically scale with sqrt(time) for a semi-infinite solid, which is why decarb depth grows quickly at first and then more slowly. The diffusion coefficient itself increases with temperature, so higher forge heats grow decarb much faster than lower heats. [R8]

Figure 4. Qualitative scaling of decarb depth with time (illustrative).

4.3 Practical controls

Controls that actually work in a bladesmith scale shop:

• Tune forge atmosphere. A reducing atmosphere reduces scale.

• Keep heats short. Do not soak the blade at forging temperature unless the steel needs it for carbide solution.

• Use surface protection when appropriate (anti-scale coatings).

• Budget grinding allowance. If you cannot control atmosphere, you must remove decarb mechanically.

even if your geometry is perfect, surface chemistry can quietly lower effective carbon at the edge and produce a blade that hardens inconsistently.

5. Temperature measurement and control in a small shop

5.1 Why color is unreliable

Color depends on ambient light and emissivity. Two steels at the same temperature can look different if one is scaled, one is clean, or if one is in shadow. Use color only as an emergency fallback.

5.2 Better methods

Preferred hierarchy:

1) Thermocouple in the forge hot zone.

2) Thermocouple in a sacrificial coupon placed next to the blade.

3) Calibrated IR thermometer used with consistent surface condition.

4) Magnet as a rough checkpoint only.

repeatability is built on measurement, and measurement is how you separate actual temperature from what the steel appears to be doing under shop lighting.

6. Published forging windows for common knife steels

The table below lists published guidance for several steels. Use it as a boundary map. If your steel is not listed, consult the manufacturer datasheet for hot working.

| Steel family | Example steel | Max forging temp | Min forging temp | Notes | Ref |

| Plain/low alloy | 5160 | 2200°F (1205°C) | 1600°F (870°C) | Stop above minimum; normalize near 1600°F. | R3 |

| Plain carbon | 1084 | 2150°F (1177°C) | 1500°F (816°C) | Finish above minimum; normalize after forging. | R4 |

| High carbon | 1095 | 2100°F (1149°C) | 1500°F (816°C) | Avoid low temp edge forging; carbide networks can tear. | R5 |

| High C, Cr | 52100 (VIM-VAR) | Not over 1950°F (1066°C) | Reheat early | Control time at temp; avoid overheating and grain growth. | R13 |

| Martensitic stainless | 420 | 2000-2200°F (1097-1204°C) | Do not forge below 1650°F (900°C) | Preheat 1400-1500°F; slow cool; anneal. | R14 |

6.1 Notes on why these windows differ

Differences are not arbitrary. Chemistry changes the position of Ac1 and Ac3 or Acm, the amount and type of carbides, and hardenability. This is why stainless often requires controlled cooling and post-forge annealing, while 5160 is more forgiving.

forging and heat treat limits are alloy dependent, so “I always forge at this color” fails as soon as you change steel family or section thickness.

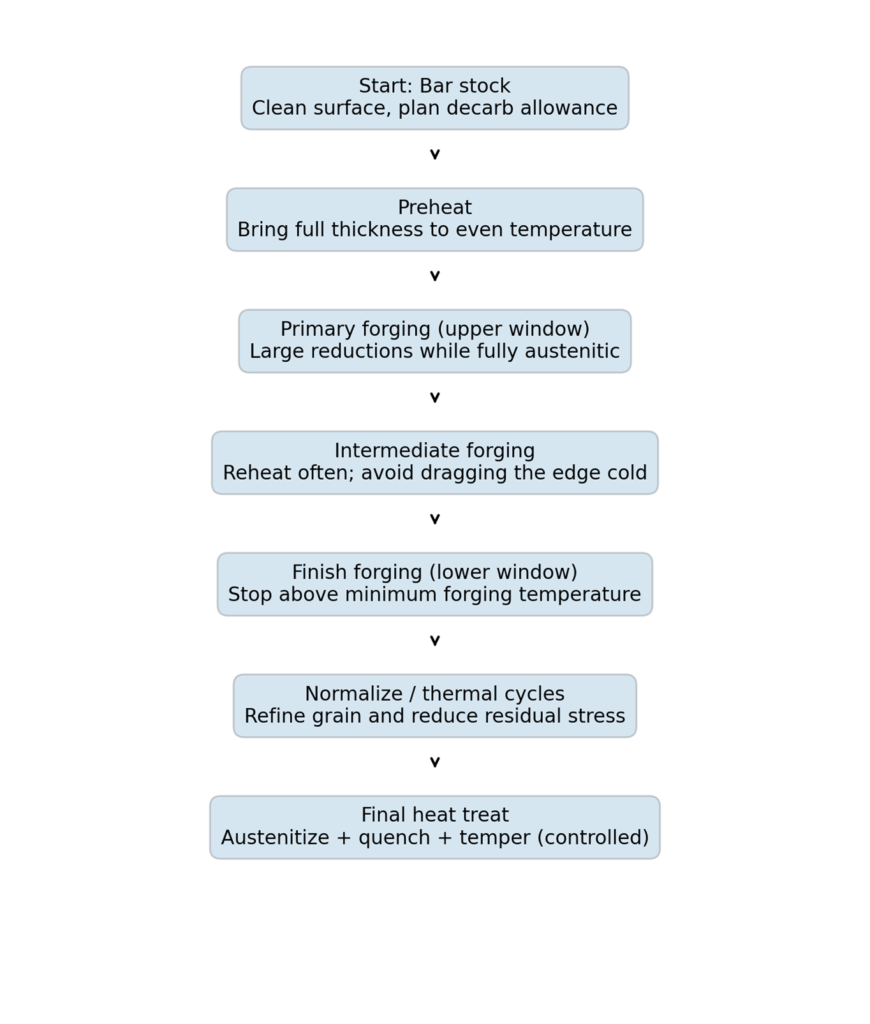

7. A forging strategy that maps to metallurgy

7.1 Sequence your work by temperature

A practical sequence for blades:

• High heat in austenite field: move volume.

• Mid heat: refine shape, correct alignment.

• Lower heat above minimum: final straightening and light planishing.

Stop before the edge is forced into the transformation band.

7.2 Reheat discipline: thin edges lie to you

Thin edges cool faster than thick spines. A blade can look hot overall while the last 0.5 mm of the edge has already dropped below the safe band. Reheat earlier than you think you need when forging bevels.

7.3 Post-forge thermal cycles are part of forging control

Normalization and thermal cycling after forging can reduce residual stress and refine prior-austenite grain size. If you forged near the upper end of the window, plan corrective thermal work.

Figure 3. Forging control is a sequence, not a single temperature.

these symptoms are not generic bad luck. They map back to specific temperature range errors and timing choices.

8. Troubleshooting by symptom

- Edge splits during drawing: Edge dropped below minimum forging temperature; high strain at thin section; cracks start at carbides, inclusions, or sharp geometry.

- Blade warps during bevel forging: Mixed phase deformation due to thermal gradient; edge in transformation band while spine is austenitic.

- Surface does not harden: Decarburized skin from oxygen rich heats; grind past the skin or improve atmosphere control.

- Brittle chipping after heat treat: Excess grain size from overheating; insufficient normalization; hardness too high for use case.

- Intergranular cracking or burnt grain: Severe overheating near incipient melting or hot shortness; scrap the piece for critical knives.

FAQ

- ?Why is steel color a bad temperature indicator for blades

Color is not a measurement because brightness depends on ambient light and surface emissivity, and emissivity changes with scale, decarb, and surface finish. On blades, the edge also cools much faster than the spine, so the blade can look “hot enough” while the edge has already dropped into a mixed phase or warm working band. - ?If the steel is nonmagnetic, does that mean I am safely above the criticals

Not reliably. Steel loses magnetism at the Curie point near 770 C, and austenite is also nonmagnetic, so the same observation can come from different mechanisms. In fast heating, the surface can be nonmagnetic while the core is still partly ferrite plus pearlite, so you can still be forging a mixed phase cross section even though the magnet test says “go.” - ?Why do exact temperatures matter if I am only off by a little

Because the penalties are not linear. Grain growth rate increases rapidly with temperature, decarb accelerates with higher heat and time, and the transformation band between Ac1 and Ac3 or Acm creates mechanical mismatch through the cross section. Small overshoots or undershoots can shift you into a different damage mechanism even if the steel still looks visually similar.

About the author

Yashar Mousavand writes technical bushcraft knife content focused on repeatable shop variables: temperature, time, section size, and steel specific data. This page cites manufacturer and technical sources where exact temperatures matter so readers can verify the numbers.

References

R1: University of Utah, Lecture 19 (eutectoid temperature ~727°C): https://my.eng.utah.edu/~lzang/images/lecture-19.pdf

R2: University of Michigan MSE, Curie point of iron (~770°C): https://mse.engin.umich.edu/internal/demos/curie-point-of-iron

R3: American Bladesmith Society, 5160 working sequence: https://www.americanbladesmith.org/community/heat-treatment-and-metallurgy/5160/

R4: American Bladesmith Society, 1084 working sequence: https://www.americanbladesmith.org/community/heat-treatment-and-metallurgy/1084/

R5: American Bladesmith Society, 1095 working sequence: https://www.americanbladesmith.org/community/heat-treatment-and-metallurgy/1095/

R6: Heat Treat Doctor, Grain size specifics: https://heat-treat-doctor.com/documents/GrainSize.pdf

R7: Zhou et al., Austenite Grain Growth (example data): https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12666-023-03031-y

R8: Thermal Processing, MacKenzie (2023), decarburization and diffusion: https://thermalprocessing.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/0723-HS.pdf

R10: ScienceDirect Topics, Zener-Hollomon parameter: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/zener-hollomon-parameter

R11: Metals (MDPI), DRX concepts and critical strain: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4701/10/1/135

R12: Springer PDF, hot tearing and incipient melting near solidus: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/bf02652466.pdf

R13: Carpenter Technology, CarTech 52100 datasheet: https://carpentertechnology.com/hubfs/7407324/Material%20Saftey%20Data%20Sheets/52100.pdf

R14: Carpenter Technology, Type 420 datasheet: https://carpentertechnology.com/hubfs/7407324/Material%20Saftey%20Data%20Sheets/420.pdf